3 GENERATION HOUSE

Client: NYC HPD

Location: East Harlem, NYC

Program: Residential

Anticipated Construction Cost: $1,117,696

Cost Per Square Foot: $296

Aging in Place

A great deal of ink is given over in architectural writing and thinking about the maintenance and accommodation of architectural context in the built environment. We as architects have long believed that if we took care of the material continuity of the city, the social and cultural continuity would follow. Maintaining whole communities has been the responsibility of the social safety net.

We are proposing an infill typology that looks to address one aspect of maintaining communities – allowing seniors to age in place while staying in their building or at least their neighborhood.

Row House Evolution

The design of the classic New York City row house – three or four-family, with an elevated stoop leading to a parlor floor, and a lower entry to a garden level, has defined the shape and character of our residential neighborhoods. Honed through replication, the design creates a unique social relationship to the street. The stoop and the small front yard define a semi-public territory; the slight distance keeps the passer-by at bay but is close enough to encourage friendly interaction. The myriad of interactions with the public, from postal and package delivery to the unannounced visitor, are accomplished gracefully. The parlor level is elevated enough above the street to create some privacy within. Patterns of use have changed over the last century, but the typology has proven remarkably resilient.

We have reached a juncture, however, where the brownstone is no longer feasible as a multi-family housing infill paradigm. The lots as originally platted are too narrow for our modern egress requirements, and the efficiency of the shared structural party wall is lost, creating an even smaller building footprint. The split entrance of the brownstone has proved irreconcilable with the urgency of providing accessible apartments (in a city that is already full of accessibility challenges). The fire escape, for decades an appendage that solved evolving egress requirements, is no longer viable. With these challenges alone, replacing the density of occupancy of the original row houses is nearly impossible; if the neighborhood survives gentrification, the infill lots become single-family houses better suited to the constraints.

Higher density high-rise residential is certainly a goal, but is difficult to achieve without razing large swaths to create large blocks. Higher-density infill often arrives like an alien presence – often built up to the street wall, it lacks the gracious semi-public buffer of the row house stoop. Ground-floor residences, placed right next to the public way, are uncomfortable and dark because they must keep their shades drawn at all times. Even when the new buildings match the material or architectural context of the existing neighborhood, they do not fit the social context.

Embracing Anomaly

If the grid made New York City great, it is the anomalies that make the City magical. Where the rhythm of the street facades breaks down because of loss of individual buildings over time, these holes have often been filled in humble ways: community gardens, single-story garages, or simply annexed by the neighbors for enlarged yards that give us a glimpse into the backyard sanctum.

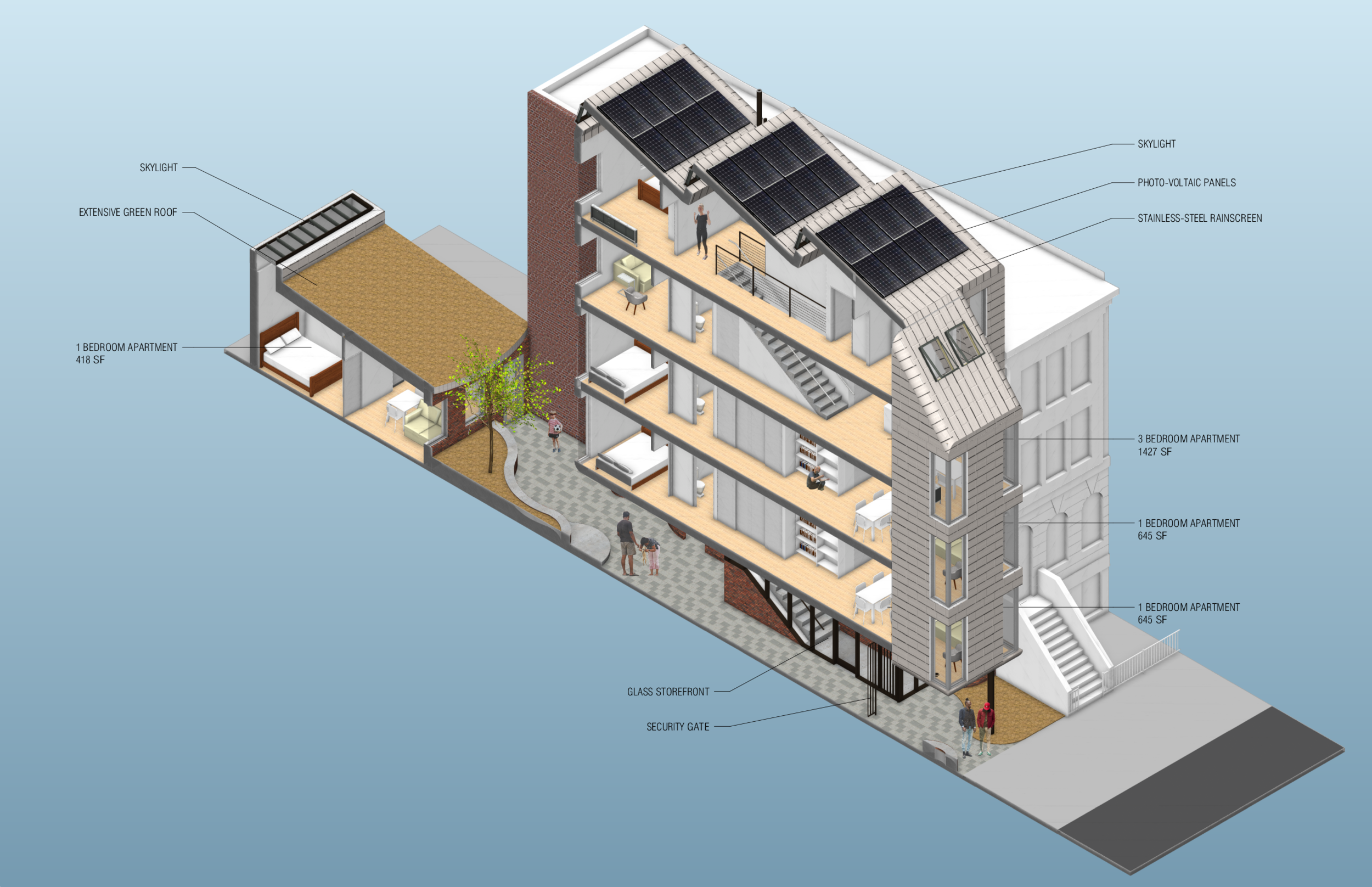

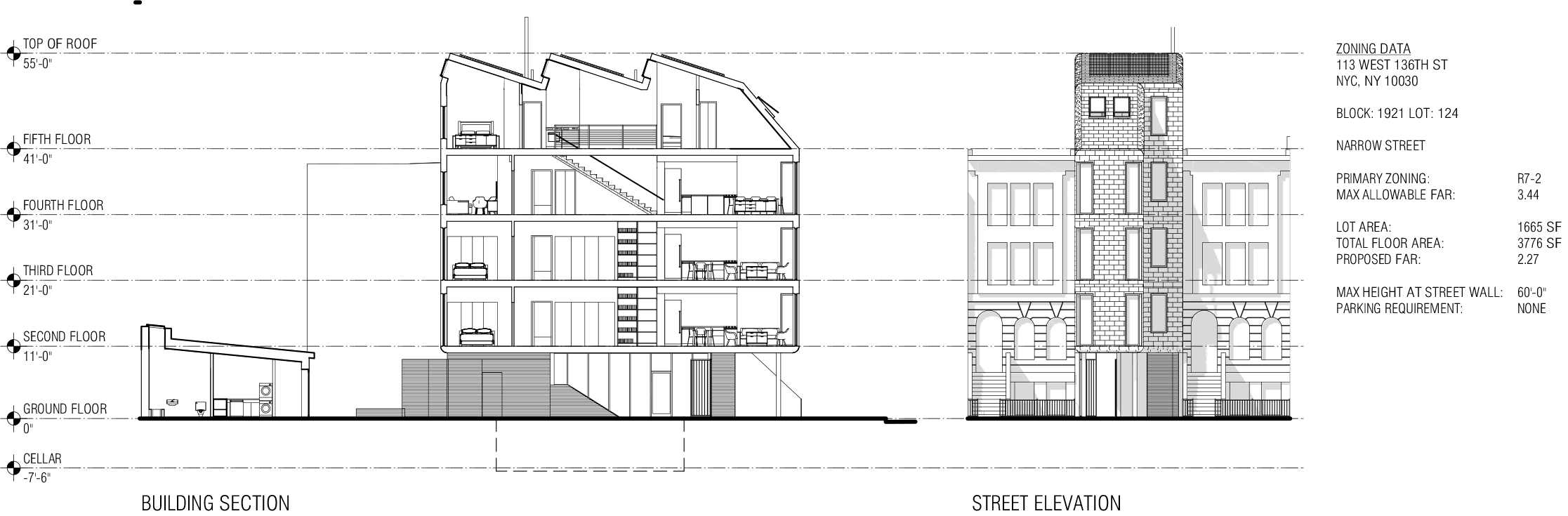

We are proposing an anomalous typology specifically to suit narrow infill sites such as 113 West 136th Street. The ground floor apartment is pushed to the back of the lot, creating a semi-public front yard and pass-thru space, and a 20 foot deep shared inner courtyard with a fully-accessible one bedroom unit in the back. The main floor plate is kept relatively shallow, allowing daylight to penetrate through the depth of the building. The rear unit is topped with an extensive green roof, creating a visual amenity for the upper units and neighbors.

This configuration, with the smaller accessible unit, also lends itself to aging in place. Rather than holding onto a multiple-bedroom unit in order to stay in their neighborhood, seniors are able to move into the ground-floor unit, where their proximity to the shared outdoor space for the unit keeps them included in the social milieu of the building and facilitates neighbors visiting or checking on them. The building then becomes a diagram for a possible residential lifecycle: starting in one of the two lower one bedroom units as a single person or young couple, and then moving to the upper three bedroom with the arrival of kids. As the children grow up and move out, the resident could move into the accessible unit in the back and stay in their home for as long as possible.

We believe that this similar typology could be applied to other similar narrow and deep infill lots, provided that there is sufficient depth to provide separation between the front and rear buildings. It would require relaxation of the R7 zoning rear yard requirements, but we believe that a single-story building has scarcely more impact on the neighboring yards than a six-foot fence or backyard shed.

Materiality and Construction Methods

The second floor of the 3_Generation House rests on a concrete flat slab, supported by columns on one side and reinforced CMU on the other. The upper floors would be light-gauge steel joists resting on CMU load-bearing walls. By keeping the cellar to a minimum required for furnace and utility meters and keeping away from the neighboring foundations, we hope to keep expensive and risky shoring of and underpinning of the adjacent buildings to a minimum.

The exterior walls on the ground floor are clad with brick. Above the ground floor, the exterior walls and soffits would be clad with a stainless-steel tile rainscreen over a combination of exterior and batt insulation. The roof of the main building would be clad with the same stainless-steel tiles over a cold liquid-applied roof and batt insulation. The roof of the rear building would be an IRMA roof with insulation and 4 inches of growth medium over a cold liquid-applied roof system.

The building is sprinklered throughout.

Building Performance and Sustainability

Storm run-off from both roofs would be collected in a tank in the courtyard for gardening use and slow release into the sewer system. The angle of the main roof monitors facilitates both north-facing skylights but also provides an ideal tilt for rooftop photo-voltaic panels. Heating is provided with a building-wide hydronic system through baseboard radiators, and cooling is addressed by a pair of in-ceiling split systems per floor with the compressors concealed behind a brick screen wall in back. Air exchange is through four HRV (heat recovery ventilators) per floor, which also provide make-up air for the exhaust fans.